Australia is home to a plethora of world-renowned chefs and a vibrant, diverse food scene, yet the nation has never appeared on the list of over 40 countries and territories where the Michelin Guide has established a presence.

At Sixpenny, one of the most prestigious restaurants in the Stanmore suburb of Sydney, Executive Chef Tony Schifilliti notes that the conversation regarding the “Little Red Guide” is a perennial hot topic within the hospitality industry. “Anyone working in this sector can tell you exactly what Michelin is and how much influence it commands,” Schifilliti says.

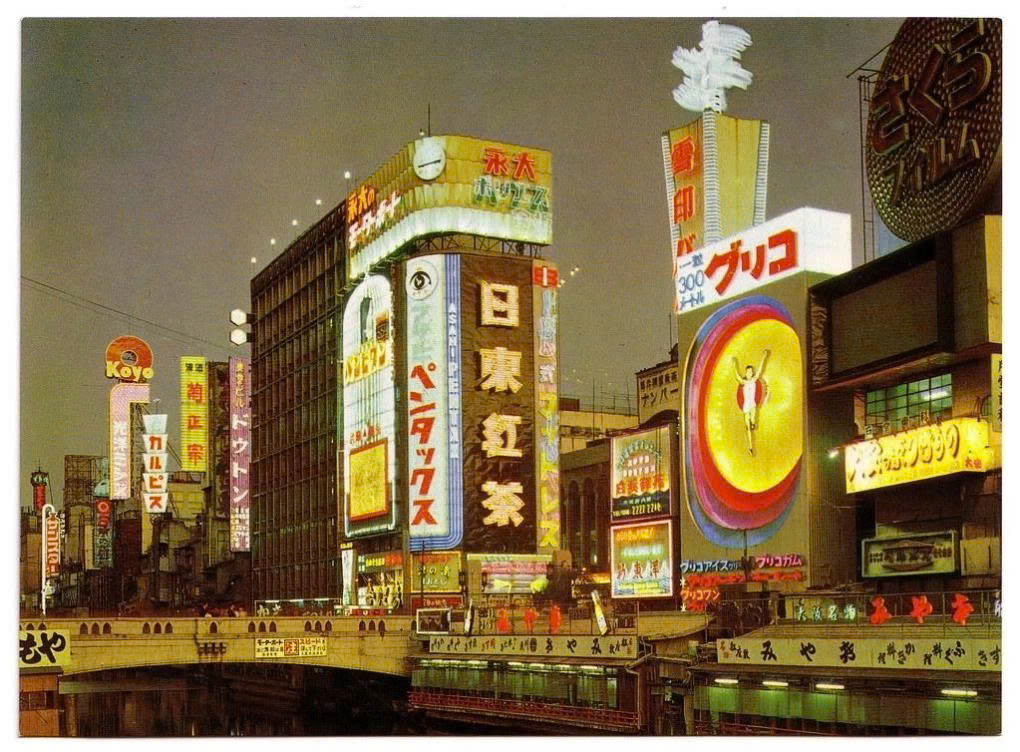

The reality remains a point of frustration for local gourmands: it is impossible to find a Michelin-listed restaurant on Australian soil. As of early 2026, the Michelin Guide has expanded its reach significantly across the globe. In the Asia-Pacific region, Michelin planted its flag in Japan as early as 2007, followed by Hong Kong (2008), Thailand (2017), Vietnam (2023), and most recently, the Philippines (2025). Australia, however, remains a notable void on the map.

The Michelin Guide was born in 1900, the brainchild of tire manufacturing brothers André and Édouard Michelin. Originally, the guide was a free resource intended to help motorists find car mechanics, gas stations, and places to eat or rest while on the road—essentially a marketing ploy to encourage more driving and, consequently, more tire wear. It wasn’t until 1926 that the guide began awarding its first “stars” to fine-dining establishments, eventually evolving into the world’s most coveted culinary barometer.

Chef Schifilliti believes that the arrival of Michelin in Australia would solve a critical issue: the hospitality labor shortage. The prestige associated with these stars would provide a powerful incentive for talented young chefs to stay and build their careers at home rather than moving abroad to seek international recognition. Furthermore, he argues it would offer a unique opportunity for restaurants in rural and remote areas to gain visibility among international tourists who plan their travels around the guide’s recommendations.

Joining the Michelin ecosystem would bring strategic benefits to the country, firmly placing Australian gastronomy on the global stage. “We have many exceptional restaurants recognized domestically, but on the international battlefield, we often seem to be overlooked,” Schifilliti remarks.

Despite the undeniable potential, the path to bringing Michelin to Australia is fraught with obstacles. The primary point of contention among tourism authorities and industry experts is the actual economic return on investment (ROI) compared to the massive upfront costs.

Professor Richard Robinson from Northumbria University in the UK—a former chef who has conducted extensive research into consumer behavior—notes that the “passive culinary tourist” segment is actually quite small. These are the travelers who visit major cities specifically to sit in “fine dining” restaurants.

Professor Robinson points to a significant shift toward “proactive culinary tourists.” This group prioritizes authentic experiences, cultural storytelling, and the provenance of food, often referred to as the “paddock-to-plate” (or farm-to-table) model. For these travelers, a Michelin star on a window might be less appealing than the chance to pick ingredients directly from a garden or engage in conversation with a local farmer.

This divergence in consumer trends has placed Australian authorities in a difficult economic position. To bring the Michelin Guide to a new country, state tourism bodies and the federal government typically must pay millions of dollars in licensing and operational fees. In an era where public spending is under intense scrutiny, these figures have become a major roadblock, causing discussions to stall for years.

Tourism Australia has been in intermittent discussions with Michelin since 2016, but a final agreement remains elusive. Currently, the national budget for tourism is prioritized toward existing marketing campaigns and infrastructure rather than investing in a costly new platform like the Michelin Guide.

For its part, Michelin maintains that its selection process is “entirely independent” and that restaurants cannot pay to buy stars. However, the organization has yet to announce a specific timeline for the Land Down Under. Instead, they have shifted their focus nearby.

“Our current focus is preparing for the launch of the Michelin Guide New Zealand in mid-2026, which marks our first step into the Oceania region,” a representative for the Michelin Guide stated. This move has left many in the Australian industry wondering why the smaller neighbor across the Tasman Sea was chosen first.

As of now, Michelin’s only official footprint in Australia is the “Michelin Keys” system, launched in 2024 to evaluate and rate luxury hotels. While the country’s hospitality sector continues to innovate and win domestic accolades, those wishing to see Michelin stars on Australian tables must wait for a formal response from regulatory bodies and the guide itself.

Until then, Australia’s world-class dining scene will continue to thrive on its own terms—relying on local critics and a loyal customer base—while the “Little Red Guide” remains just out of reach.

(According to ABC News, Delicious)