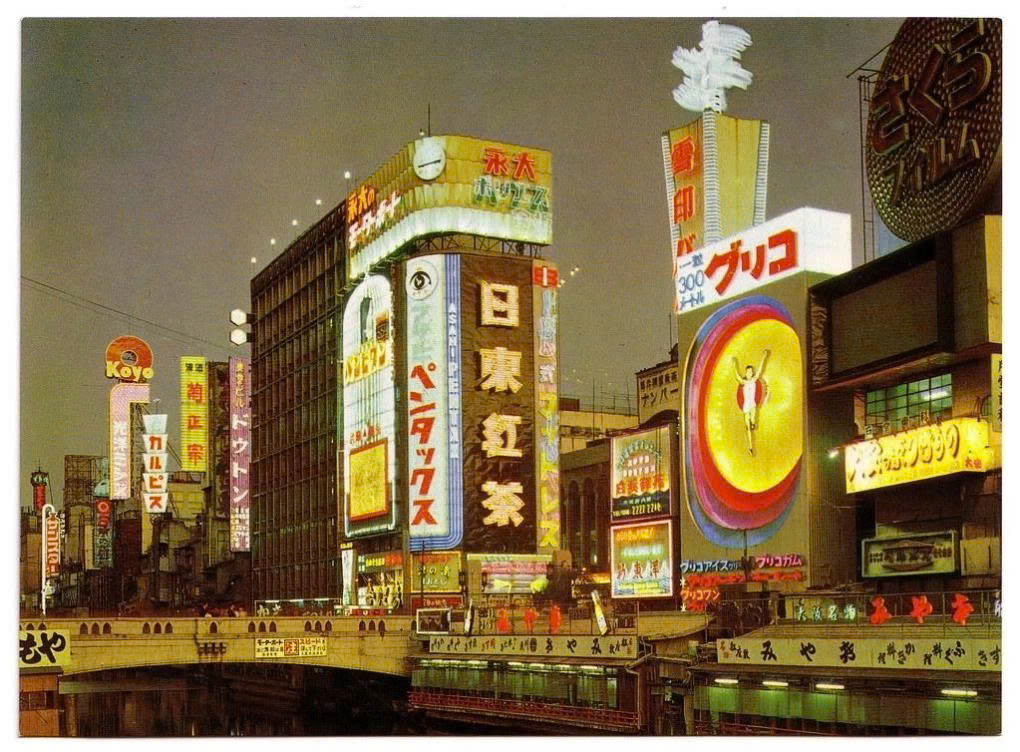

As the final hours of December 31st approach and the resonant echoes of Joya no Kane (temple bells) ring out across Japan, a singular tradition unites the nation: a bowl of Toshikoshi Soba. Whether served steaming hot in a savory broth or chilled on a bamboo tray, this simple buckwheat noodle dish is more than just a late-night snack. It is a profound ritual of transition, steeped in centuries of symbolism and spiritual meaning.

The tradition of eating soba on New Year’s Eve dates back to the mid-Edo period (1603–1867). Known as Toshikoshi Soba, which literally translates to “year-crossing noodle,” the practice began among townspeople and soon spread across the country. Today, it remains one of the most enduring customs in Japanese culture, representing a collective wish for health, wealth, and a clean slate.

While other noodles like udon or ramen are prized for their chewy elasticity, soba is uniquely fragile. Made from buckwheat flour, it snaps easily under the teeth. To the Japanese, this physical property carries a deep metaphysical meaning:

Breaking with the Past: Because soba is easy to cut, eating it symbolizes “cutting off” the hardships, debts, and misfortunes of the past year. It is a literal and figurative way to prevent the bad luck of the old year from following you into the new one.

Longevity and Resilience: Conversely, the long, thin shape of the noodle represents a long and healthy life. Furthermore, the buckwheat plant itself is incredibly resilient; it can withstand harsh wind and rain during its growth, symbolizing the strength needed to face the coming year.

Beyond health and spiritual cleansing, soba is inextricably linked to financial fortune. According to historical records from the Soba Association, goldsmiths and lacquer artisans in old Japan used fine soba flour to gather up scattered gold dust and flakes in their workshops. Because the flour was so effective at “collecting gold,” soba became a talisman for attracting wealth. Eating it on New Year’s Eve is believed to bring financial prosperity and ensure that “gold” stays within the household.

The preparation of Toshikoshi Soba varies significantly depending on regional preferences and family traditions. Generally, there are two primary styles:

Kake-soba (Hot): Popular in colder regions and during the chilly winter nights, the noodles are served in a hot broth made from katsuo dashi (bonito stock), soy sauce, and mirin. In Tokyo, the broth is typically dark and salty, while in Osaka and western Japan, a lighter, more delicate dashi is preferred.

Mori-soba (Cold): For those who prefer the pure taste of buckwheat, the noodles are boiled, chilled, and served on a zaru (a slatted bamboo tray). It is accompanied by a dipping sauce (tsuyu), wasabi, and scallions.

Common toppings also carry their own meanings. Tempura shrimp are a favorite because their curved shape resembles the arched back of an elderly person, further emphasizing the wish for a long life. Scallions (negis) are added not just for flavor, but because the word sounds like the Japanese verb “to soothe” or “to pray,” symbolizing peace in the household.

While there is flexibility in how you eat your soba, there is one strict rule: you must finish your bowl before midnight.

Leaving even a single strand of noodle on your plate as the clock strikes twelve is considered a bad omen. Culturally, it suggests that you are carrying your debts and the “burdens” of the previous year into the next. To ensure a fresh start and financial stability, every drop of soup and every bit of noodle should be consumed while the old year is still technically in progress.

Beyond the spiritual and symbolic, there is a practical reason why soba remains the New Year’s Eve meal of choice. After days spent Osoji (ritual deep-cleaning the home) and preparing complex Osechi-ryori (New Year’s feast) dishes, families are often exhausted. Soba is quick to cook and easy on the stomach, providing a moment of calm and nourishment before the festivities of New Year’s Day begin.

For professional chefs like Hideyuki Okamoto, who has spent three decades perfecting the craft, New Year’s Eve is the busiest day of the year. Some high-end establishments, like Okamoto’s, even serve soba topped with edible gold leaf on December 31st to lean into the theme of prosperity. “Gold is a symbol of luck in Japan,” his family explains. “We add it to offer our customers the best possible start to their year.”

If you find yourself in Japan during the New Year, joining this tradition is easy. Soba shops are ubiquitous, ranging from standing stalls in train stations to high-end traditional restaurants. Just remember to slurp your noodles loudly—it’s a sign of appreciation for the chef and is said to enhance the aroma of the buckwheat!

(According to Tokyo Weekender, livejapan, JNTO)