In Turkey, after finishing their coffee, people often turn the cup upside down onto the saucer, let it cool, and then “read the shape of the coffee grounds” to find meaning.

In Turkey, coffee comes with a touch of destiny. To call Turkish coffee “a drink” is an understatement. Because it is a ritual, a conversation, and fortune-telling.

Turkish coffee is “more than a drink,” says Seden Dogan, a University of South Florida lecturer and a native of northern Turkey. Dogan calls coffee in her homeland a “bridge” that connects people through life, both joy and sorrow. Coffee is the drink for meeting and conversation in Turkey. In many countries, when two long-separated friends want to meet and talk, they say, “Let’s go for coffee,” which in Turkey is equivalent to saying, “Come over, I will invite you for a cup of coffee.”

The brewing ritual requires precision and care, using a small, long-handled pot called a cezve, placed over a heat source (stove, hot coals, or hot sand). The finest coffee grounds are slow-cooked to create a rich flavor and a beautiful layer of foam on the surface, which signifies quality.

A proper cup of Turkish coffee must be served hot, retaining the foam, along with a glass of water and a piece of lokum (Turkish delight). The water helps cleanse the palate, while the lokum balances the bitterness of the coffee.

The way to enjoy the coffee is equally important. Although served in small cups, Turkish coffee must be drunk slowly and calmly, not rushed like an espresso. This allows the coffee grounds to settle at the bottom of the cup and remain there.

When the coffee cup is empty, it is time for the ritual of tasseography, also known as “coffee ground reading.” The cup is turned upside down onto the saucer, allowed to cool, and then the shapes and symbols seen in the grounds are “read” for meaning. The stories are often interpreted spontaneously; for example, if the grounds resemble a fish, it means you will have good luck, while a bird signifies a journey.

Although fortune-telling in general is not encouraged in Islamic culture, reading coffee grounds is seen as a “symbolic and playful interpretation” and a “communal ritual,” according to Kylie Holmes, author of “The Ancient Art of Tasseography.”

“Coffee fortune-telling” is considered a pleasure when enjoying the drink. Tasseography is an act of storytelling. Dogan says she often spends an hour reading coffee grounds, creating stories and focusing on positive outcomes because people “like to hear good things about themselves.”

The Turkish coffee ritual also weaves its way into other social practices. During the pre-nuptial process, the future bride will brew and serve Turkish coffee to the groom and his family. To test the groom’s character, she adds a significant amount of salt to his coffee. If he drinks it without complaint, it proves his patience, maturity, and his worthiness of her.

Turkish coffee is the “ancestor” of all modern coffees, a nearly 500-year-old piece of history, recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

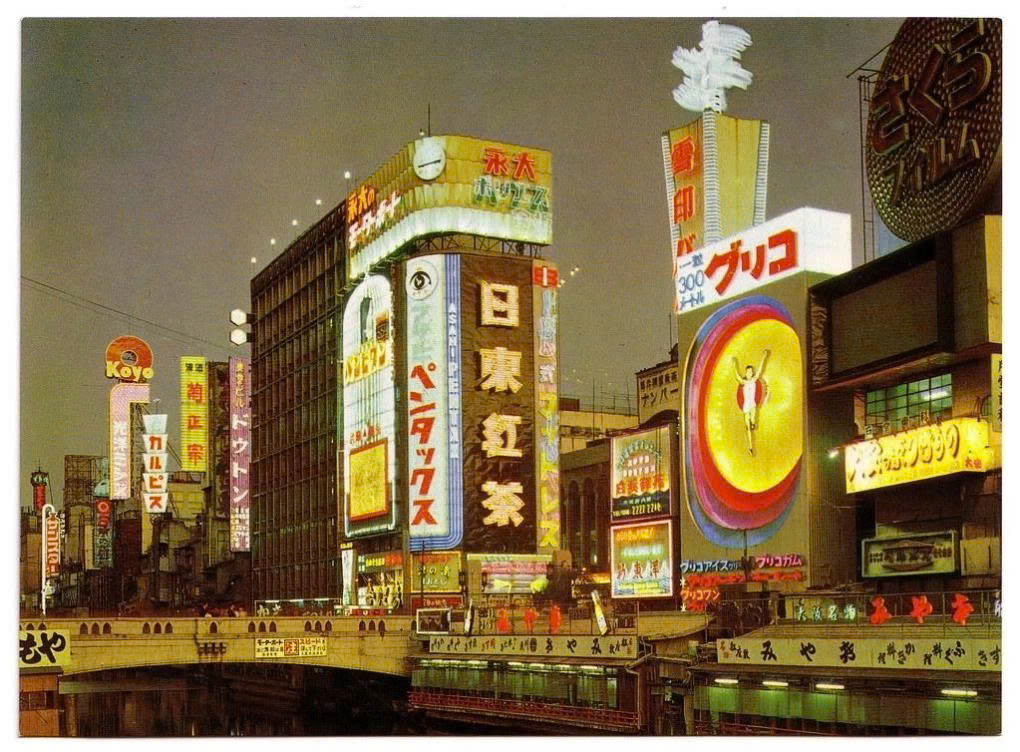

Turkish coffee originated in Yemen. In the 15th century, Sufi mystics are believed to have drunk coffee to stay awake during nights of prayer. When Sultan Süleyman, the longest-reigning ruler of the Ottoman Empire, captured Yemen in 1538, coffee began to gain a foothold in the Ottoman Empire. Within a year, coffee became popular in the ancient city of Constantinople, now Istanbul.

In the 1550s, the first coffee houses began to appear in Istanbul, documented by historian Ibrahim Pecevi in his book “Pecevi History.” The drink’s popularity quickly reshaped cultural life. The Ottoman method of preparing coffee became the hallmark of traditional Turkish coffee. According to culinary researcher Merin Sever, the fundamental difference between Turkish coffee and other coffees is the cezve-ibrik (the cooking method). Coffee here is not “brewed” but “cooked” in water like a soup, resulting in a drink that does not require filtering.

Coffee houses also caused controversy. Religious scholars and political leaders in Asia and Europe viewed them as places where subversive activities and frivolous conversations took place. The Governor of Mecca, Hayır Bey, banned coffee in the city in 1511, an edict that lasted 13 years. Ottoman sultans also repeatedly shut down coffee houses for similar reasons. However, these shops never completely disappeared.

For an authentic experience, visitors should seek out places that brew coffee using the “cezve” on hot sand. A proper cup of coffee must be served piping hot, with a thick, smooth foam, accompanied by a glass of water and a piece of “lokum” (Turkish delight) to balance the bitterness.

In Istanbul, visitors can go to Hafız Mustafa, Mandabatmaz on İstiklal Street, or Nuri Toplar in the Egyptian Bazaar. If you want a more modern experience, Hacı Bekir in the Kadıköy district is a suggestion.

To try “fortune-telling,” you can visit the Sultanahmet area. But the best way, according to locals, is to befriend a local and ask them to “read” the fascinating story waiting at the bottom of your coffee cup.

(According to CNN)