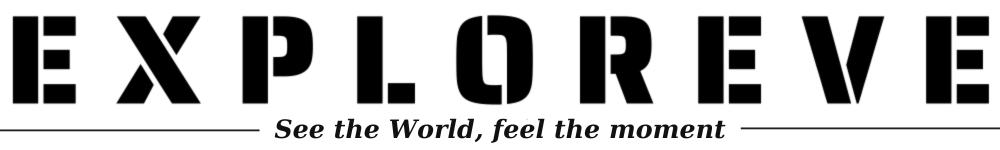

During the Vietnamese New Year, the tradition of đi lễ chùa đầu năm (visiting pagodas) serves as an indispensable spiritual thread woven into the nation’s cultural fabric. For the Vietnamese people, this is far more than a simple religious ritual; it is a moment of profound connection between the mundane world and the sacred realm. As the air fills with the fragrance of incense and the rhythmic resonance of temple bells, this pilgrimage becomes a sacred time to discard past hardships and embrace the hope of a ‘Vạn Sự Như Ý’ future.

1. The Deep-Rooted Significance: Why Millions Flock to Temples

In Vietnamese culture, đi lễ chùa đầu năm represents the “Hành Hương” (pilgrimage) to the land of the Buddha. As the very first sunbeams of the Lunar New Year touch the earth, spiritual sanctuaries from the bustling streets of Hanoi to the quiet corners of the Mekong Delta become beacons of hope.

The Philosophy of “Tâm Linh” (Spirituality)

The act of visiting a pagoda is rooted in the belief that the start of the year sets the tone for the remaining 365 days. By entering the “Gate of Virtue,” one seeks to align their energy with the compassion and wisdom of the Buddha.

- Seeking Peace (Cầu An): Unlike many Western traditions that focus on material gain, the primary intent for many Vietnamese is to pray for An Lạc (inner peace) and health for their parents and children.

- Cultural Continuity and Ancestral Connection: For families, it is a living classroom. Parents use this time to educate younger generations about Vietnamese gratitude, the law of cause and effect (Karma), and the importance of modesty.

- Spiritual Rebirth (Gột Rửa Tâm Hồn): The scent of agarwood (Trầm Hương) acting on the senses helps purify the soul after a hectic, often stressful year. It is a psychological “reset” button that fosters resilience.

2. Master the Art of Preparation: “Lễ Vật” and Sincerity

To ensure your đi lễ chùa đầu năm is merit-filled, one must understand that preparation is a form of meditation. In Buddhism, the intention behind the gift is more valuable than the gift itself.

The Offering Tray: Symbolism over Substance

According to ancient Buddhist tradition, “Tâm Thành” (sincerity of heart) is the most important offering. However, physical symbols—known as “Lễ Vật”—serve as physical manifestations of that devotion:

- Hương, Hoa, Đăng, Trà: These four elements are essential.

- Hương (Incense): Represents the transmission of prayers to the heavens.

- Hoa (Flowers): Symbols of impermanence and beauty. Use Lotus, Chrysanthemums, or Lilies; avoid wildflowers or pungent blooms.

- Đăng (Candles/Lights): Representing wisdom that dispels the darkness of ignorance.

- Trà (Tea): Symbolizing clarity and mindfulness.

- The Five-Fruit Tray (Mâm Ngũ Quả): A vibrant display of fruits representing the five elements (Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, Earth) and the desire for “Phúc, Lộc, Thọ, Khang, Ninh” (Wealth, Luck, Longevity, Health, and Peace).

- Vegetarian vs. Non-Vegetarian (Lễ Chay vs. Lễ Mặn): This is a critical point of etiquette. The Buddha and Bodhisattvas only accept Lễ Chay (vegetarian offerings). Meat, alcohol, and salty dishes should never be placed in the Main Hall (Chính Điện). If you bring such items, they are strictly reserved for the shrines of “Đức Ông” (The Guardian) or “Thánh” (Saints) located in separate areas of the temple complex.

3. Dressing for the Divine: The “Pháp Phục” Etiquette

The “Search Intent” for many modern pilgrims revolves around the social and respectful aspects of temple attire. In the age of social media, maintaining the sanctity of the pagoda while looking elegant is a delicate balance.

When đi lễ chùa đầu năm, your clothing is a reflection of your inner respect:

- The Rule of Three: Clothes should cover the shoulders, chest, and knees. Avoid sheer fabrics or tight-fitting “athleisure.”

- The Rise of “Áo Lam”: Many Vietnamese now opt for Áo Lam or Pháp Phục—simple, loose-fitting linen sets in earthy tones like grey, brown, or soft blue. These garments promote a sense of equality; in the eyes of the Buddha, there is no rich or poor.

- The Traditional Ao Dai: For the first days of Tet, the Áo Đai remains the gold standard. It honors national identity while providing a dignified silhouette perfect for the solemnity of a pagoda.

4. The Sacred Ritual: A Step-by-Step Guide to Worship

Many visitors feel lost in the sprawling architecture of Vietnamese temples. Understanding the “spiritual flow” ensures you don’t miss any vital steps in the ritual of đi lễ chùa đầu năm.

The Order of Ceremonies

- The Outer Altar (Nhà Bái Đường/Đức Ông): Traditionally, you must “report” your presence to the Guardian Deity (Đức Ông) first. He is the protector of the temple’s lands.

- The Main Hall (Chính Điện): This is the most sacred space, housing the Tam Bảo (The Three Jewels). Here, you offer your main prayers and perform the Lễ Phật (prostrations).

- The House of Patriarchs (Nhà Tổ): Here, you pay respects to the generations of monks who built and maintained the temple.

- The Rear Hall (Nhà Hậu): Where the deceased (whose photos are placed at the temple) are honored.

Note: Always enter through the side doors—the “Gate of Virtue” on the right or the “Gate of Wisdom” on the left. The central door is traditionally reserved for high-ranking dignitaries or the spirits themselves. When walking inside, move clockwise (pradakshina) as a sign of respect.

5. Modern Taboos: “Những Điều Kiêng Kỵ” in the 21st Century

As environmental awareness grows, the customs of đi lễ chùa đầu năm have evolved. To practice “Right Mindfulness,” observe these updated rules:

- Environmental Stewardship: The old habit of “Bẻ Cành Hái Lộc” (breaking tree branches for luck) is now considered a “bad merit” act as it harms nature. Modern pilgrims “pick luck” by receiving a small red envelope from a monk or buying a symbolic salt packet at the gate.

- Money and Merit: Do not place small currency notes into the hands of statues. This is seen as “bribing” the divine and creates a cluttered, disrespectful environment. Always use the Tiền Công Đức (Donation Boxes).

- Digital Silence: While capturing the beauty of a temple is tempting, avoid “selfies” with the Buddha or filming during a live chanting session. Keep your phone on silent to preserve the Thanh Tịnh (absolute stillness) of the space.

6. Destinations for the 2026 Spring Pilgrimage

If you are organizing a journey for đi lễ chùa đầu năm, Vietnam offers diverse spiritual landscapes:

- Northern Vietnam (The Land of Festivals):

- Yen Tu Mountain: The cradle of Truc Lam Zen Buddhism.

- Huong Pagoda (Chùa Hương): A scenic boat journey through limestone caves.

- Bai Dinh Temple: A magnificent complex holding many Asian records.

- Central & Southern Vietnam (The Path of Serenity):

- Thien Mu (Hue): Iconic and historic, overlooking the Perfume River.

- Vinh Nghiem (HCMC): A hub for urban Buddhists seeking a moment of peace.

- Ba Den Mountain (Tay Ninh): Home to the tallest bronze Buddha statue in Asia, a must-visit for 2026.

The act of đi lễ chùa đầu năm is a beautiful synthesis of ancient faith, refined art, and national identity. It is a moment where time slows down, and the spiritual “Self” takes precedence over the material “I.” By following these guidelines, you not only preserve a thousands-year-old tradition but also ensure your New Year begins with a heart full of merit, wisdom, and peace.