On a bustling evening in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, a few coins left on a table by American tourists stumped the staff at an izakaya.

In Japan, where omotenashi – the spirit of selfless hospitality – is a source of national pride, tipping was once seen as an insult. However, with the booming number of international visitors, this custom is starting to take root, creating a lot of changes. Still, the Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO) states on its website that tipping is not a common practice in bars, cafes, restaurants, taxis, or hotels.

According to JTB Tourism Research, Japan welcomed more than 21.5 million international visitors in just the first half of this year. This influx has forced many restaurants and hotels to adapt to the unfamiliar “tipping culture.” The Gyukatsu Motomura restaurant chain, for instance, was initially confused when many tourists started leaving tips. “Foreign guests, especially from countries with a tipping culture, frequently leave tips,” a company representative shared.

The consequences go beyond social etiquette, as tips are considered taxable income in Japan and must be declared. To address this, Gyukatsu Motomura installed “tip boxes” at nearly all of its 24 branches last year. The money is strictly controlled, counted twice a month, and then allocated to a welfare fund for employees. Each store collects an average of 20,000-30,000 yen (US$135-200) per month.

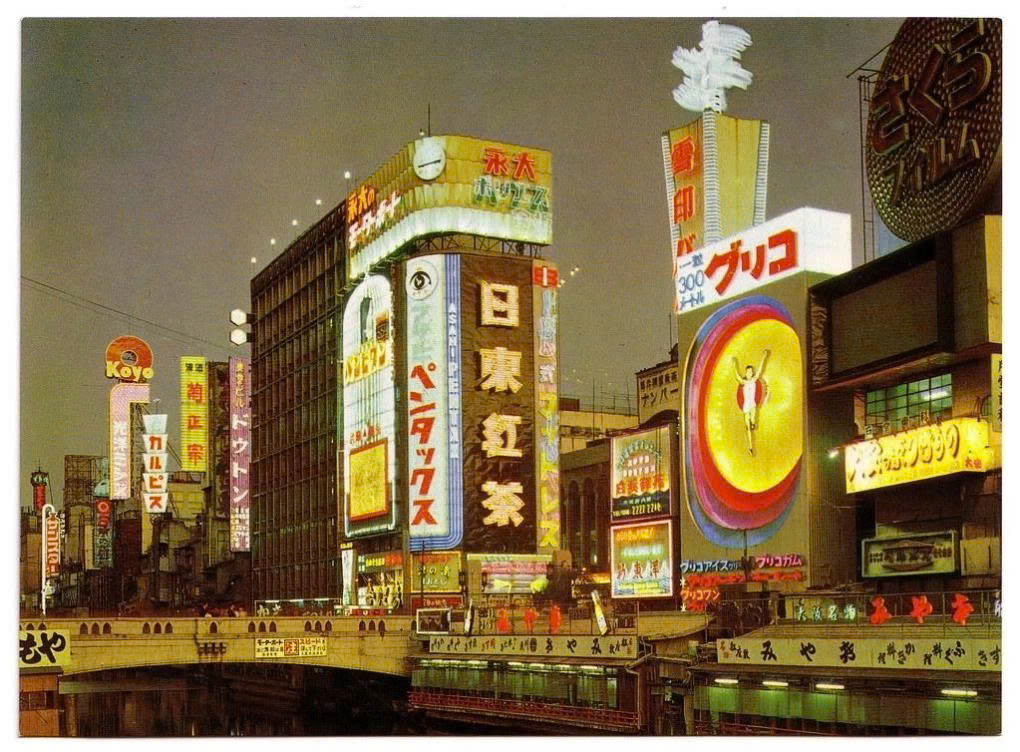

The restaurant management app Dinii now allows customers to add a tip of up to 25% to their bills. This system is available at more than 900 establishments, especially in popular tourist spots like Shinjuku (Tokyo) and Namba (Osaka). One waitress even revealed she received 70,000 yen in a single month through the app.

Some restaurant owners say the extra income helps motivate staff and create a positive atmosphere. However, the Japanese public remains cautious. “We don’t want tipping culture to be imported into Japan,” one diner complained. On social media, many people worry whether the tips truly go to the employees or if they are kept by the restaurants.

Amid rising living costs, Japanese households now spend nearly 30% of their income on food – the highest level in 43 years, according to The Japan Times. Many experts believe that tips could partially support the service industry, which suffers from low wages and labor shortages. Last year, the average wage in the accommodation and food services sector was only 269,500 yen (US$1,700), the lowest among all industries, according to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.

“In the West, service is considered something to be paid for. In Japan, people are uncomfortable with placing a monetary value on hospitality,” said Professor Yoshiyuki Ishizaki, a tourism marketing expert at Ritsumeikan University.

However, he warned that labor productivity would be difficult to improve if the “service is free” mindset doesn’t change. “Ideally, businesses should include a service charge in the price and ensure the profit is reasonably distributed to the employees,” he added.

According to SCMP

- Top 20 Fruits You Should Try in Vietnam: A Fruity Adventure

- Guide to Korean Templestays: Finding Serenity in the Mountains

- How Much Salary Need for a Comfortable Digital Nomad Life in Vietnam?

- 15 Amazing Family-Friendly Activities in Hanoi Vietnam

- The Egyptian Government Has Suspended Numerous Camel Riding Tours