Travelers arriving in Nepal in 2026 might find themselves in a state of temporary confusion. Upon purchasing a snack at a local grocery store or receiving a receipt at a government office, they might notice expiration dates or transaction records marked with the year 2083. While the rest of the world follows the Gregorian calendar, moving steadily through the third decade of the 21st century, the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal is officially living more than half a century ahead.

The 57-year gap between Nepal’s official time and the Common Era (CE) is not a glitch in the matrix or a sign of futuristic technology. Instead, it is a profound testament to a deeply rooted culture where time is not merely a linear progression of numbers, but a rich tapestry woven from history, spirituality, and the natural rhythms of the Earth.

The official calendar of Nepal is known as Bikram Sambat (BS). This ancient Hindu calendar system predates the Gregorian calendar by approximately 56.7 years. It is named after King Vikramaditya, a legendary emperor of ancient India. According to historical lore and tradition, the King established this new era to commemorate his victory over the Sakas (Scythian invaders).

Unlike the Gregorian calendar, which is a solar calendar, Bikram Sambat is lunisolar. This means it calculates time by observing both the phases of the Moon and the movement of the Sun. The lunar aspect is crucial for determining the precise dates of religious festivals, while the solar cycle dictates the agricultural seasons. Because the BS era began in 57 BC, the Nepalese year is always ahead of the Western year by 56 or 57 years, depending on the month.

While Bikram Sambat is the official national standard used for government administration, education, and the press, it is far from the only system in use. Nepal is a mosaic of ethnic groups and traditions, many of which maintain their own ways of measuring time:

- Nepal Sambat: This unique calendar belongs to the Newar community—the indigenous inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley. It began in 879 AD and is primarily used today for religious ceremonies and cultural festivals.

- Lhosar (Tibetan Calendar): In the high Himalayan regions, communities such as the Sherpas and Tamangs follow the Tibetan lunar calendar. They celebrate “Lhosar” (New Year), though the specific date varies among different ethnic subgroups.

- The Gregorian Calendar (AD): To stay connected with the global community, Nepal uses the Gregorian calendar for international trade, aviation, diplomacy, and the tourism industry.

This plurality results in “multi-dimensional” calendars in Nepalese homes. A single square on a wall calendar might contain three or four different sets of numbers, ensuring that no spiritual duty, government deadline, or cultural celebration is overlooked.

One of the most fascinating features of the Bikram Sambat calendar is that the number of days in a month is not fixed. In the Western world, we know that June always has 30 days and July has 31. In Nepal, however, a month can vary between 29 and 32 days from year to year.

These variations are determined by professional astronomers and astrologers who calculate the exact time the Sun enters different zodiac signs. Consequently, the Nepalese people cannot rely on memory alone to know how many days are in the current month; they must consult the official calendar published by the government’s Panchanga Nirnayak Samiti (Calendar Determination Committee) each year.

The Nepalese New Year, or Naya Barsha, typically falls on the 13th or 14th of April. This transition marks the end of spring and the beginning of summer, signaling a new cycle for the nation’s farmers.

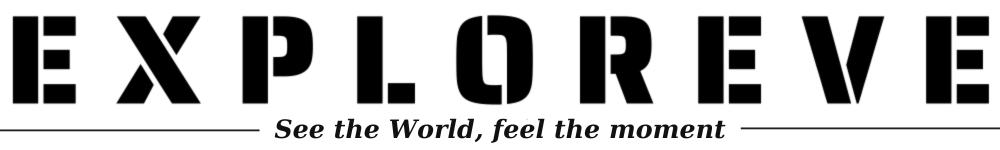

For the people of Nepal, the calendar is much more than a tool for scheduling meetings. It is a spiritual and agricultural compass. The country’s most significant festivals—such as Dashain (the celebration of good over evil), Tihar (the festival of lights), and Holi (the festival of colors)—are all dictated by the lunisolar positions of the BS calendar.

Because the months reflect the climatic shifts of the Himalayas so accurately, the calendar tells farmers exactly when to sow seeds, when to transplant rice during the monsoon, and when to harvest. By maintaining this ancient system, Nepal preserves a traditional rhythm of life where community activities and religious devotion remain synchronized with the cycles of nature.

For the uninitiated traveler, Nepal’s time system can be a source of bewilderment. It is common to see a bottle of water produced in “2081” with an expiry date in “2082.”

When filling out official paperwork at a local police station or purchasing bus tickets in remote districts, the dates on the forms may be written entirely in Bikram Sambat. However, the Nepalese are famously hospitable and accustomed to international visitors. In tourist hubs like Thamel in Kathmandu or the lakeside city of Pokhara, hotel staff and travel agents almost always provide dates in the Gregorian format to accommodate foreign guests.

The most important tip for travelers is regarding festivals. Because festivals follow the lunisolar BS calendar, their Gregorian dates shift every year. If you visited Nepal for the Holi festival in March one year, it might fall in late February or later in March the following year. Checking a current Nepalese calendar is essential for anyone wanting to witness these vibrant cultural events.

Beyond the mechanics of dates and months, the persistence of the Bikram Sambat calendar carries deep political and cultural weight. Throughout history, while much of Southeast Asia fell under colonial rule, Nepal remained one of the few nations that was never fully colonized.

Retaining their own calendar is seen as a symbol of cultural identity and spiritual sovereignty. While the Gregorian calendar is used as a bridge to the outside world for commerce and tourism, Bikram Sambat remains the heartbeat of the nation’s internal life. It is a daily reminder that while Nepal is a participant in the modern global era, it remains firmly rooted in a heritage that began long before the Western world’s calendar even existed.

So, when you visit Nepal, don’t just think of it as a trip to a different country. Think of it as a journey into the future—a place where the year 2083 is already happening, fueled by the wisdom of the past.

(According to Spiritualculture, Turistas)