You’ve booked the flight, mapped out the UNESCO sites, and scrolled through countless photos of Hạ Long Bay. You’re ready for Vietnam, a country that captivates millions with its vibrant chaos, stunning landscapes, and unforgettable cuisine. Yet, as you prepare to immerse yourself in the culture, you’re looking for something more—you’re seeking to belong, if only for a moment. You want to understand the rhythm of life here, the silent rules that govern daily interactions, and, most importantly, how to navigate this society with tôn trọng (respect).

This article is your exhaustive cultural handbook, written from a local’s perspective to give you the real, nuanced insights necessary to move beyond being just a visitor. The rules of Vietnamese etiquette are not arbitrary; they are deeply rooted in a philosophical and historical foundation. Understanding this foundation is the key to unlocking genuinely warm and memorable interactions. This guide serves as your cultural passport, transforming your experience from a mere sightseeing tour into a series of meaningful exchanges.

1.The Two Pillars of Vietnamese Conduct

The entire framework of Vietnamese etiquette rests on two major cultural, both of which you must internalize:

Confucianism: This ancient system, emphasizing morality, duty, and respect for social hierarchy, dictates that respect flows upward. Age and seniority always take precedence over youth, a dynamic immediately visible in greetings and titles. This is why you must always greet the elderly first, why proper titles are paramount, and why humility is a highly prized virtue.

Giữ Thể Diện (Saving Face/Maintaining Dignity): This is arguably the most crucial concept in all of Vietnamese social interaction. Face is the combination of a person’s honour, prestige, and dignity within their community and social group. Causing someone to Mất Thể Diện (Lose Face) by openly criticizing them, yelling, or making them feel embarrassed is one of the gravest social errors you can commit. Your mission as a traveler is to ensure that you maintain your own face and, critically, never cause a local to lose theirs, even inadvertently.

RELATED: Discover Vietnamese Culture: Unveiling the Soul of a Nation

2. The Foundational Etiquette: Greetings and Social Hierarchy

The very first interaction sets the tone for your entire relationship. Getting the greeting right is the clearest indication that you’ve done your cultural homework and are serious about respecting the local way of life.

Do: Master the Art of the Vietnamese Greeting (Chào)

The simplest rule is often the most profound: Always initiate with a sincere smile. A smile is the universal language that breaks down barriers faster than any phrase.

| Etiquette | Why It Matters |

| Greet with a Smile and a Slight Bow/Nod | This is the safest, most universal, and immediate sign of goodwill and humility. In the absence of a shared language, this gesture alone communicates respect and openness. |

| Let the Local Initiate the Handshake | Handshakes are common in urban business and formal male-to-male settings. However, do not automatically extend your hand to a woman or an elderly person; defer to their lead. If they simply nod or clasp their hands, mirror that gesture. |

| Use the Double-Handed Gesture | This is a non-verbal power move of respect. When giving or receiving anything—money, a gift, a business card, or even a glass of water—use both hands or your right hand supporting the left wrist. This communicates sincerity and high respect, particularly when dealing with an elder or a host. Failure to do this with an elder can signal indifference or haste. |

| Use “Xin Chào” | The phrase means “Hello.” Though sometimes shortened in casual speech, using the full “Xin Chào” (Pronounced: Sin Chào) is polite and appreciated by locals who see you making the effort. |

Don’t: Underestimate the Power of Pronouns and Titles

This is where the structure of the Vietnamese language comes into play. Unlike English, Vietnamese pronouns (I, you) are based on the relationship, age, and seniority between speakers, not just gender. Misusing them is the quickest way to sound unintentionally rude, as it disrupts the accepted social hierarchy.

- The Concept: In Vietnam, you don’t call someone “you.” You call them “Older Brother,” “Younger Sister,” or “Grandmother” to define your relationship with them. This system is called honorifics.

- The Problem: Using the generic “bạn” for “you” with someone older than you can be highly disrespectful, as it implies they are your equal or subordinate, erasing the crucial element of age-based respect.

For an authentic trip learn the few key elements that matter most.

You don’t need to speak fluently, but learning these titles is non-negotiable for respectful interaction:

| Title | Pronunciation | Used For | Context/Implication |

| Anh | Ahn | Men slightly older than you | Addressing a waiter, shopkeeper, or male tour guide. Signals respect for seniority. |

| Chị | Chee | Women slightly older than you | Addressing a waitress, vendor, or female colleague. Shows respect for a peer/superior. |

| Em | Em | Anyone notably younger than you | Addressing a younger server, vendor, or child. Used by the older party in the conversation. |

| Bác | Bahk | People your parents’ age (Uncle/Aunt) | Use this out of deep respect for an older person, especially a vendor or taxi driver. |

| Ông / Bà | Ohng / Bah | Elderly people (Grandfather/Grandmother) | The highest title of respect for seniors, showing deference to age. |

| Cô | Coh | Women your parents’ age (Aunt) | Often used instead of Bác in Southern Vietnam, sometimes reserved for teachers. |

Tip: When in doubt about someone’s age, it’s always better to default to a slightly older, more respectful title (Anh or Chị). A small, polite error of overestimating respect will be instantly forgiven; underestimating it may cause offense. When addressing a group of people, always try to make eye contact with each person and use the appropriate title, starting with the oldest.

Do: Respect the Elders

Due to the enduring and powerful influence of Confucianism, the elderly are the absolute foundation of Vietnamese society and command the utmost deference and respect.

- Priority of Entrance: In any situation—whether entering a room, a car, or sitting down at a table—the elder should go first and receive the most prominent or comfortable seat. Always stand up when an elderly person enters the room.

- Serving and Seating: During a meal, the elder is served first. This rule is absolute. In a group setting, if you are unsure who is the most senior, quietly ask your host or guide.

- Listening: When an elder speaks, listen intently and respectfully. Avoid interrupting or contradicting them directly. If you disagree, use soft language, starting with an honorific and phrasing your view as a question or an observation, not a challenge.

- Body Language: Ensure your posture is respectful when near an elder; avoid slouching, putting your hands in your pockets, or having a casual demeanor that could be mistaken for indifference.

RELATED: The Essential Guide to Understanding Vietnamese Etiquette for Travellers

3. Public Behavior and Body Language: The Don’ts of Da Street

Moving through a busy Vietnamese city requires more than just navigating the traffic; it requires navigating subtle, non-verbal social codes. These rules are vital for Giữ Thể Diện (Saving Face)—both yours and others’. Violating them can turn a friendly interaction sour instantly.Don’t: Violate the Sacred/Profane Body Rules

Vietnamese culture has strict, though often unspoken, rules regarding different parts of the body, rooted in spiritual beliefs.

- The Head (The Sacred): The head is considered the seat of the soul, the most sacred part of the body, and often where the spirit resides. NEVER touch someone’s head, especially a child’s, even if you mean it affectionately (e.g., ruffling hair). This is a severe violation of personal space and dignity, akin to insulting their spirit.

- The Feet (The Profane): The feet are considered the lowest and dirtiest part of the body, associated with earth and the mundane. NEVER use your feet to point at a person, a sacred object, an altar, or food. Don’t rest your feet on tables or chairs, and be mindful not to point the soles of your feet toward someone when sitting (e.g., crossing your legs with one sole facing a person).

Don’t: Show Excessive Emotion or Affection in Public

Humility, restraint, and modesty are highly regarded Vietnamese virtues. Western-style public expression is often seen as inappropriate or childish.

- Public Displays of Affection (PDA): Intimate kissing and hugging in public are highly discouraged and often viewed as inappropriate or embarrassing to others. Holding hands is generally acceptable in modern urban centers like Hà Nội and Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh (Entities), but keep affection minimal and always observe the local environment. Avoid any behavior that draws undue attention.

- Losing Your Temper: This is one of the most critical offenses against Giữ Thể Diện. NEVER yell, shout, argue loudly, or point your finger at someone, especially in a stressful situation (e.g., negotiating a price, dealing with a traffic misunderstanding). Raising your voice ensures that both you and the person you are arguing with lose face, making the situation much worse and making it almost impossible to resolve the issue favorably.

- The Local’s Way (Do): Remain calm, speak softly, and use a pleasant tone, even if you are frustrated. A calm demeanor is a powerful signal of maturity and respect, which is the most effective way to resolve conflicts.

- Loudness: In general, keep your speaking voice moderate. Loud, boisterous chatter, especially in quiet areas like temples, buses, or hospitals, is considered disruptive and ill-mannered.

Don’t: Use Aggressive or Disrespectful Gestures

- Pointing: Avoid pointing with a single index finger at a person. Use your whole hand, palm up, as a gentler, more inclusive gesture when indicating a person or a direction.

- Hands on Hips or Crossed Arms: Standing with your hands on your hips or with your arms crossed across your chest can be interpreted as defiant, challenging, or arrogant. Maintain a relaxed, open, and humble posture.

- Waving: When waving goodbye or calling someone over, use a gentle downward motion with your entire hand, not an up-and-down “come here” gesture, which can be seen as condescending.

RELATED: Cultural Shocks in Vietnam: A Tourist’s Survival Guide

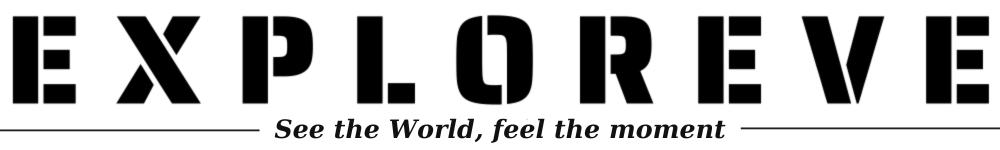

4. Religious and Sacred Sites Etiquette (Temples, Pagodas, Homes)

Vietnam is home to a rich tapestry of beliefs, including Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Ancestor Worship. Showing respect in sacred and private spaces is a fundamental expectation of any traveler.

Do: Dress and Act Appropriately at Sacred Sites

- The Dress Code (Do): When visiting any pagoda, temple, shrine, or even a Catholic church, you must cover your shoulders, chest, and knees. Pack a shawl, sarong, or light jacket specifically for this purpose. Revealing clothing, including shorts, miniskirts, or tank tops, is considered deeply disrespectful.

- Removing Gear (Do): Remove your shoes, hats, and sunglasses before crossing the threshold into the main sanctuary or Hall of Worship of a temple or pagoda. Look for a shoe rack outside.

- Conduct: Walk slowly and speak in a whisper or remain silent. Do not chew gum or eat inside the sacred space. Keep your phone on silent.

- Photography (Don’t): Do not take photos when people are actively praying or performing a ritual. Do not turn your back to the main Buddha statue, deity statue, or altar for a selfie. Do not climb on statues or architecture.

- Touching Offerings (Don’t): Never touch or move any offerings (fruit, flowers, money) placed on the altars, as these are reserved for the spirits or deities.

RELATED: How to Visit a Vietnamese Pagoda with Respect and Understanding

Do: Follow Protocol When Visiting a Vietnamese Home

Being invited into a local’s home is a high honour and a powerful indicator of trustworthiness and acceptance. Treat the experience with utmost care, as you are entering their private sanctuary.

- Shoes (Do): Always remove your shoes and leave them neatly outside the front door or on the designated rack unless explicitly told otherwise by the host. This symbolizes leaving the dirt of the outside world behind.

- The Ancestor Altar: The altar, typically adorned with fruit, flowers, and incense, is the most sacred spot in the house. Acknowledge it briefly with a slight bow of the head, and never point at it or place any personal items near it.

- Gifts (Do): Bring a small gift for the host—fresh fruit, sweets, imported chocolates, or a small novelty item from your home country are excellent choices. This gesture is called “quà biếu” and is a sign of appreciation.

- Gift Don’ts: Don’t give sharp objects (knives, scissors) as they symbolize cutting a relationship. Don’t wrap gifts in black or white paper (colors of funerals/mourning). Red, yellow, or colourful paper is best.

- Seating (Do): Wait to be shown where to sit. The host will assign seating based on seniority. Do not take the most comfortable or prominent seat unless directed to.

- Hospitality (Do): The host will be incredibly generous. Accept offers of tea, beer, or food graciously. If you must refuse, do so gently after the first offer, explaining you’re full or have a delicate stomach, but do not persistently refuse multiple offers, as this can insult the host’s generosity.

5. Dining Etiquette: Sharing and Serving

Vietnamese food is a sensory adventure, but enjoying it with good manners is an integral part of the experience. Meals are inherently communal and reinforce family and community bonds.

Don’t: Commit the Chopstick Taboo (The Cardinal Rule)

The use of chopsticks (a crucial cultural tool Entity) carries one of the most powerful social superstitions you must avoid at all costs.

- The Cardinal Rule (Don’t): NEVER stick your chopsticks vertically upright into a bowl of rice. This position exactly resembles the incense sticks placed upright in a bowl of sand on an altar, symbolizing a funeral rite. It is a major bad omen and extremely disrespectful to the host and the deceased.

- Resting Chopsticks (Do): Place them horizontally across the top of your bowl or on a provided chopstick rest. Never leave them on the table parallel to the edge or pointing at another person.

- Serving and Sharing: When transferring food from a communal dish to your bowl, use the serving spoon or the blunt, back end of your chopsticks. Don’t use the end that goes in your mouth to serve others.

- Pointing (Don’t): Don’t use chopsticks to point at people or gesture across the table.

Do: Follow Meal Flow and Serving Protocol

- Waiting (Do): Just like social greetings, the oldest person at the table must be the first to start eating. Wait until they begin or invite you to start. This is non-negotiable in a family setting.

- Serving Others (Do): It is a beautiful and expected gesture of care and good manners to pick a desirable piece of food (like a shrimp or a choice cut of meat) and gently place it into the bowl of a companion, especially the elder.

- Holding the Bowl (Do): It is perfectly acceptable and expected to lift your small rice bowl or noodle bowl close to your mouth while eating. This is often necessary to prevent food from dropping and is a sign of good manners here.

- Finishing the Meal (Expertise): Unlike Western cultures where finishing your plate signals satisfaction, it is often polite to leave a small amount of rice or food in your bowl, signifying that the host provided enough food and you are completely full. If you clean the plate entirely, it can sometimes be misinterpreted as the host not feeding you enough.

- Slurping (Do): If you are eating soup or noodles (like Phở or Bún Chả—major Food Entities), a gentle slurp is acceptable and may even signal your enjoyment of the delicious food to the cook.

RELATED: Ancestor Worship Traditions in Vietnam

Do: Navigate the Vietnamese Drinking Culture

Social drinking, whether tea or alcohol, often involves group toasts and collective participation, reinforcing unity.

- The Toast (Do): If someone raises a glass, you must participate. Learn the cheer: “Một, Hai, Ba, Vô!” (One, Two, Three, Cheers/Drink!) (Pronounced: Mộ, Hai, Ba, Yo!) You must clink glasses and take a sip collectively with the group. Refusing a toast entirely, especially from the host, can be seen as antisocial.

- Refilling (Do): Never let someone’s glass remain empty. It is a sign of good hospitality to monitor and refill the glasses of those around you, starting with the highest status person, before refilling your own.

- Pacing: If you don’t wish to drink too much alcohol, discretely signal that you will only sip after the toast, rather than downing the entire glass. Your politeness will be appreciated.

RELATED: How to Eat Pho Like a Vietnamese: A Guide for First-Timers

6. Transactional and Practical Etiquette (Markets, Money, Traffic)

These are the rules that govern your daily life and keep transactions running smoothly. This section is vital for fulfilling the Preparational Intent of the traveler and ensuring smooth interactions with the working populace.

Do: Practice the Art of Polite Bargaining (Mặc Cả)

- Where to Bargain: Bargaining is expected and a cultural institution in local markets (chợ), street stalls, souvenir shops, and when hiring non-metered taxis or xe ôm (motorbike taxis). Do not bargain in formal restaurants, supermarkets, or malls. Prices in established stores are generally fixed.

- The Approach (Do): Bargain with a smile, good humour, and politeness. View it as a friendly game, not a confrontation. Start low (perhaps 30-40% below the asking price) and aim to settle around 20-25% lower, especially for mass-produced tourist items. For some big markets like Ben Thanh Market, you can start 60-65 % below the asking price.

- The Don’t (Losing Face): Don’t agree on a price and then walk away without buying. This is a severe loss of face for the vendor, implies you wasted their time, and is incredibly rude. If you start the process, be prepared to buy.

- Money Etiquette (Do): Always try to pay with smaller denomination bills (Vietnamese Đồng – VND—Currency Entity). Handing a vendor a 500,000 VND note for a 20,000 VND purchase is a major inconvenience, as they must scramble for change, and can sour the mood.

RELATED: Shopping in Ho Chi Minh City: Markets, Malls & Souvenirs

Do: Understand Vietnamese Traffic

Vietnam’s traffic, dominated by the relentless flow of motorbikes, looks chaotic but operates on its own unspoken rules based on momentum and anticipation.

- Crossing the Street (Do): Don’t run, dart, or make sudden stops. The local method is to walk slowly, steadily, and predictably across the street. The drivers are experts at anticipating your speed and will flow around you like water around a stone. Sudden, erratic movements break the flow and cause confusion or accidents.

- The Horn: The constant honking is generally not an angry gesture; it is a notice—”I am here, and I am coming past you, but I won’t hit you.” It is a vital part of the communication system.

RELATED: How to Cross the Street in Vietnam: From Tourist to Local

Do: Handle Tips and Payments with Respect

- Tipping Culture: Tipping is not mandatory in most Vietnamese service settings but is increasingly appreciated, especially for those in the tourism sector (guides, drivers, hotel staff). It is not expected in local phở shops or street stalls. A small, polite tip for a tour guide or driver at the end of a trip is a kind gesture.

- Giving and Receiving Money (Do): Always use two hands when exchanging money with an elder or a highly respected person. If using one hand, support the right elbow with your left hand as a secondary gesture of respect.

7. Navigating Sensitive Topics and Conversations

For deep, respectful engagement, you must know where the cultural landmines lie. This section provides the essential local wisdom to maintain harmony.

Don’t: Touch the Three Major Taboos

- Politics and Government (Don’t): Never openly criticize the Communist Party of Vietnam or the government. Avoid discussing sensitive topics such as historical conflicts (The Vietnam War, known here as the American War—Historical Entity), political figures, or border disputes. These topics are complex, sensitive, and often seen as deeply private. If a local brings up the topic, listen respectfully without offering strong political opinions.

- Personal Criticism (Don’t): Never directly criticize or point out a mistake a Vietnamese person has made, especially in front of others. This is the surest way to cause them immense loss of face. If you must correct someone, do so privately, gently, and with an apologetic tone. Focus on the outcome, not the person’s error.

- Money/Wealth (Don’t): Avoid showing off or boasting about your wealth, salary, or possessions. Humility and modesty are admired; excessive display of affluence can attract unwanted attention or be viewed negatively as arrogance.

RELATED: Vietnam War Sites Guided Tours: A Journey into History

Do: Understand the Nuance of “Yes”

Vietnamese culture is built on a strong principle of harmony and non-confrontation. This affects how information is communicated.

- The Avoidance of “No”: It is difficult for many Vietnamese people to give a direct, unequivocal “no” or to state a negative. They may smile, nod, or say “yes” (vâng/dạ/có) even if they mean “maybe,” “I can’t do that,” or “I don’t know.” They do this to avoid disappointing you or causing you or themselves embarrassment (losing face).

- The Local’s Way (Do): Be perceptive. If you receive a polite nod but see hesitation in their eyes, be prepared to adjust your expectation or ask the question in a different way. Do not press the issue once you feel resistance; accept the lack of clarity gracefully to maintain harmony.

Do: Use Basic Vietnamese Phrases

Making an effort to speak even a few words of Vietnamese shows immense respect for the culture and will instantly open doors and soften potentially awkward encounters.

- Xin Chào (Sin Chào): Hello.

- Cảm Ơn (Gahm Uhn): Thank you.

- Dạ / Vâng (Yah / Vung): A polite “Yes” (Use Dạ in the South, Vâng in the North).

- Xin Lỗi (Sin Lōi): Sorry / Excuse me.

- Ngon (Ngawn): Delicious (Crucial to use after a meal!).

RELATED: 50+ Basic Vietnamese Phrases for Travelers: Your Essential Guide

8. The Local’s Deep Dive: Advanced Cultural Insights

To achieve true expertise and authority, this guide delves into the more complex, nuanced aspects of Vietnamese life that truly set a respectful traveler apart.

The Dynamics of Family and Tết

The Vietnamese Family (Gia đình) is the core Entity of society, more important than the individual.

- The Tết Holiday (Lunar New Year): This is the most important holiday of the year. If you travel during Tết, be aware that most businesses close for several days, and transport is packed. It is a time for family reunion and ancestor worship. If you are invited to a local celebration, it is a tremendous honour, and you must adhere strictly to the rules of respect (greetings, gifts, seating).

- The House: The Vietnamese household often includes several generations. Showing specific respect to the Bà (grandmother) and Ông (grandfather) of the house is paramount, as they are the true heads of the household.

RELATED: Vietnam Cultural Festivals: A Celebration of Traditions and Heritage

The Role of Names and Honorifics

In formal and social settings, people are addressed by their title (Anh, Chị, Bác) followed by their first name, not their last name.

- Example: A woman named Nguyễn Thị Lan, who is slightly older than you, should be addressed as Chị Lan. Addressing her as “Ms. Nguyễn” is a Western concept and is not used here. Using a person’s first name with the correct honorific shows you view them as an individual within the social structure.

The North vs. South Etiquette Nuances

While the fundamentals are shared, subtle differences exist between the Hà Nội (Northern) and Hồ Chí Minh City (Southern) approaches, which seasoned travelers will observe.

- North (Hà Nội): Tends to be slightly more reserved, formal, and strictly hierarchical in adherence to rules and titles. PDA is less common. People may be less outwardly expressive.

- South (Hồ Chí Minh City): Generally more open, dynamic, and forgiving of minor mistakes. Rules are often relaxed in social settings, but deep respect for elders remains mandatory.

The Concept of “Làm phiền” (To Bother/Inconvenience)

Vietnamese people are innately non-imposing and highly sensitive to causing disruption. They go to great lengths to avoid làm phiền others.

- The Implication (Do): When asking for help, do so gently, and acknowledge that you are imposing on their time. A phrase like, “Xin lỗi, tôi có thể làm phiền anh một chút được không?” (Excuse me, may I bother you for a moment?) shows humility and appreciation for their time, making them far more willing to assist.

RELATED: Best Time to Visit Vietnam: Weather by Month & Tips

Vietnam is a land of incredible warmth, hospitality, and resilience. The people are genuinely welcoming to foreigners who make a sincere effort to understand and participate in their culture. The rules of etiquette outlined in this guide are not barriers; they are a sophisticated form of communication that expresses respect and humility. Your willingness to learn the titles, mind your feet, and speak softly is the ultimate form of thanks you can offer to your hosts.

Remember this final, simple instruction: When in doubt, smile, observe the locals, and apologize sincerely (Xin lỗi). Vietnamese people are immensely forgiving of cultural mistakes made by foreigners when those mistakes are clearly rooted in ignorance, not malice.

Adopting these local insights will elevate your journey from tourism to true cultural exchange, forging genuine connections that redefine your understanding of Vietnamese hospitality.